Introducing Copilot

Can you write a list in Haskell? Then you can write embedded C code using Copilot. Here’s a Copilot program that computes the Fibonacci sequence (over Word 64s) and tests for even a numbers:

fib :: Streamsfib = do"fib" .= [0,1] ++ var "fib" + (drop 1 $ varW64 "fib")"t" .= even (var "fib")where even :: Spec Word64 -> Spec Booleven w = w `mod` const 2 == const 0

Copilot contains an interpreter, a compiler, and uses a model-checker to check the correctness of your program. The compiler generates constant time and constant space C code via Tom Hawkin’s Atom Language (thanks Tom!). Copilot is specifically developed to write embedded software monitors for more complex embedded systems, but it can be used to develop a variety of functional-style embedded code.Executing

> compile fib "fib" baseOpts

generates fib.c and fib.h (with a main() for simulation—other options change that). We can then run

> interpret fib 100 baseOpts

to check that the Copilot program does what we expect. Finally, if we have CBMC installed, we can run

> verify "fib.c"

to prove a bunch of memory safety properties of the generated program.Galois has open-sourced Copilot (BSD3 licence). More information is available on the Copilot homepage. Of course, it’s available from Hackage, too.

Flight of the Navigator

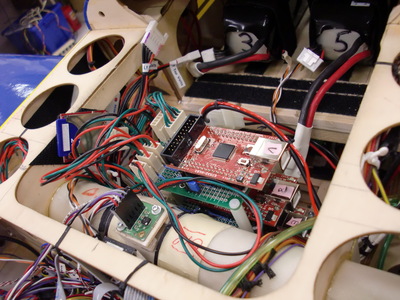

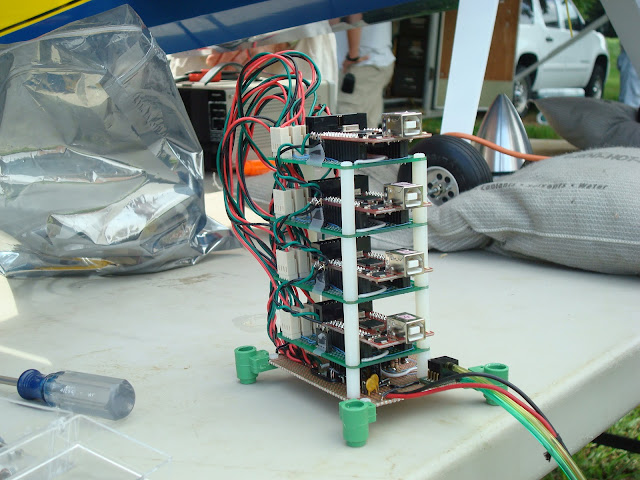

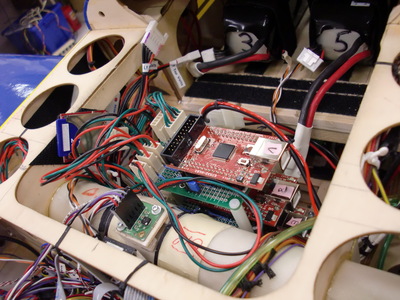

Copilot took its maiden flight in August 2010 in Smithfield, Virginia. NASA rents a private airfield for test flights like this, but you have to get past the intimidating sign posted upon entering the airfield. However, once you arrive, there’s a beautiful view of the James River.We were flying on a RC aircraft that NASA Langley uses to conduct a variety of Integrated Vehicle Health Management (IVHM) experiments. (It coincidentally had Galois colors!) Our experiments for Copilot were to determine its effectiveness at detecting faults in embedded guidance, navigation, and control software. The test-bed we flew was a partially fault-tolerant pitot tube (air pressure) sensor. Our pitot tube sat at the edge of the wing. Pitot tubes are used on commercial aircraft and they’re a big deal: a number of aircraft accidents and mishaps have been due, in part, to pitot tube failures.Our experiment consisted of a beautiful hardware stack, crafted by Sebastian Niller of the Technische Universität Ilmenau. Sebastian also led the programming for the stack. The stack consisted of four STM32 ARM Cortex M3 microprocessors. In addition, there was an SD card for writing flight data, and power management. The stack just fit into the hull of the aircraft. Sebastian installed our stack in front of another stack used by NASA on the same flights.The microprocessors were arranged to provide Byzantine fault-tolerance on the sensor values. One microprocessor acted as the general, receiving inputs from the pitot tube and distributing those values to the other microprocessors. The other microprocessors would exchange their values and perform a fault-tolerant vote on them. Granted, the fault-tolerance was for demonstration purposes only: all the microprocessors ran off the same clock, and the sensor wasn’t replicated (we’re currently working on a fully fault-tolerant system). During the flight tests, we injected (in software) faults by having intermittently incorrect sensor values distributed to various nodes.The pitot sensor system (including the fault-tolerance code) is a hard real-time system, meaning events have to happen at predefined deadlines. We wrote it in a combination of Tom Hawkin’s Atom, a Haskell DSL that generates C, and C directly.Integrated with the pitot sensor system are Copilot-generated monitors. The monitors detected

Copilot took its maiden flight in August 2010 in Smithfield, Virginia. NASA rents a private airfield for test flights like this, but you have to get past the intimidating sign posted upon entering the airfield. However, once you arrive, there’s a beautiful view of the James River.We were flying on a RC aircraft that NASA Langley uses to conduct a variety of Integrated Vehicle Health Management (IVHM) experiments. (It coincidentally had Galois colors!) Our experiments for Copilot were to determine its effectiveness at detecting faults in embedded guidance, navigation, and control software. The test-bed we flew was a partially fault-tolerant pitot tube (air pressure) sensor. Our pitot tube sat at the edge of the wing. Pitot tubes are used on commercial aircraft and they’re a big deal: a number of aircraft accidents and mishaps have been due, in part, to pitot tube failures.Our experiment consisted of a beautiful hardware stack, crafted by Sebastian Niller of the Technische Universität Ilmenau. Sebastian also led the programming for the stack. The stack consisted of four STM32 ARM Cortex M3 microprocessors. In addition, there was an SD card for writing flight data, and power management. The stack just fit into the hull of the aircraft. Sebastian installed our stack in front of another stack used by NASA on the same flights.The microprocessors were arranged to provide Byzantine fault-tolerance on the sensor values. One microprocessor acted as the general, receiving inputs from the pitot tube and distributing those values to the other microprocessors. The other microprocessors would exchange their values and perform a fault-tolerant vote on them. Granted, the fault-tolerance was for demonstration purposes only: all the microprocessors ran off the same clock, and the sensor wasn’t replicated (we’re currently working on a fully fault-tolerant system). During the flight tests, we injected (in software) faults by having intermittently incorrect sensor values distributed to various nodes.The pitot sensor system (including the fault-tolerance code) is a hard real-time system, meaning events have to happen at predefined deadlines. We wrote it in a combination of Tom Hawkin’s Atom, a Haskell DSL that generates C, and C directly.Integrated with the pitot sensor system are Copilot-generated monitors. The monitors detected

- unexpected sensor values (e.g., the delta change is too extreme),

- the correctness of the voting algorithm (we used Boyer-Moore majority voting, which returns the majority only if one exists; our monitor checked whether a majority indeed exists), and

- whether the majority votes agreed.

The monitors integrated with the sensor system without disrupting its real-time behavior. We gathered data on six flights. In between flights, we’d get the data from the SD card.

We gathered data on six flights. In between flights, we’d get the data from the SD card.

We took some time to pose with the aircraft. The Copilot team from left to right is Alwyn Goodloe, National Institute of Aerospace; Lee Pike, Galois, Inc.; Robin Morisset, École Normale Supérieure; and Sebastian Niller, Technische Universität Ilmenau. Robin and Sebastian are Visiting Scholars at the NIA for the project. Thanks for all the hard work!There were a bunch of folks involved in the flight test that day, and we got a group photo with everyone. We are very thankful that the researchers at NASA were gracious enough to give us their time and resources to fly our experiments. Thank you!Finally, here are two short videos. The first is of our aircraft’s takeoff during one of the flights. Interestingly, it has an electric engine to reduce the engine vibration’s effects on experiments.

We took some time to pose with the aircraft. The Copilot team from left to right is Alwyn Goodloe, National Institute of Aerospace; Lee Pike, Galois, Inc.; Robin Morisset, École Normale Supérieure; and Sebastian Niller, Technische Universität Ilmenau. Robin and Sebastian are Visiting Scholars at the NIA for the project. Thanks for all the hard work!There were a bunch of folks involved in the flight test that day, and we got a group photo with everyone. We are very thankful that the researchers at NASA were gracious enough to give us their time and resources to fly our experiments. Thank you!Finally, here are two short videos. The first is of our aircraft’s takeoff during one of the flights. Interestingly, it has an electric engine to reduce the engine vibration’s effects on experiments.

Untitled from Galois Video on Vimeo.

The second is of AirStar, which we weren’t invo

lved in, but that also flew the same day. AirStar is a scaled-down jet (yes, jet) aircraft that was really loud and really fast. I’m posting its takeoff, since it’s just so cool. That thing was a rocket!

Untitled from Galois Video on Vimeo.

More Details

Copilot and the flight test is part of a NASA-sponsored project (NASA press-release) led by Lee Pike at Galois. It’s a 3 year project, and we’re currently in the second year.

Even More Details

Besides the language and flight test, we’ve written a few papers:

- Lee Pike, Alwyn Goodloe, Robin Morisset, and Sebastian Niller. Copilot: A Hard Real-Time Runtime Monitor. To appear in the proceedings of the 1st Intl. Conference on Runtime Verification (RV’2010), 2010. Springer.

This paper describes the Copilot language.

Byzantine faults are fascinating. Here’s a 2-page paper that shows one reason why.

At the beginning of our work, we tried to survey prior results in the field and discuss the constraints of the problem. This report is a bit lengthy (almost 50 pages), but it’s a gentle introduction to our problem space.

Yes, QuickCheck can be used to test low-level protocols.

A short paper motivating the need for runtime monitoring of critical embedded systems.

You’re Still Interested?

We’re always looking for collaborators, users, and we may need 1-2 visiting scholars interested in embedded systems & Haskell next summer. If any of these interest you, drop Lee Pike a note (hint: if you read any of the papers or download Copilot, you can find my email).

Monitoring Distributed Real-Time Systems: A Survey and Future DirectionsAlwyn Goodloe (NIA) and Lee Pike (Galois, Inc), NASA Langley Research Center, 2010.

Monitoring Distributed Real-Time Systems: A Survey and Future DirectionsAlwyn Goodloe (NIA) and Lee Pike (Galois, Inc), NASA Langley Research Center, 2010. Dr. Lee Pike’s short abstract revisiting fault-tolerance of cyclic redundancy checks (CRCs), expanding on the work of Driscoll et al.. It introduces the concepts of Schrödinger-Hamming weight and Schördinger-Hamming distance, and argues that under a fault model in which stuck-at-one-half or slightly-out-of-spec faults dominate, current methods for computing the fault detection of CRCs may be over-optimistic.

Dr. Lee Pike’s short abstract revisiting fault-tolerance of cyclic redundancy checks (CRCs), expanding on the work of Driscoll et al.. It introduces the concepts of Schrödinger-Hamming weight and Schördinger-Hamming distance, and argues that under a fault model in which stuck-at-one-half or slightly-out-of-spec faults dominate, current methods for computing the fault detection of CRCs may be over-optimistic.